In Brief

What Is the Extent of Sudan’s Humanitarian Crisis?

A year into the civil war in Sudan, more than eight million people have been displaced, exacerbating an already devastating humanitarian crisis.

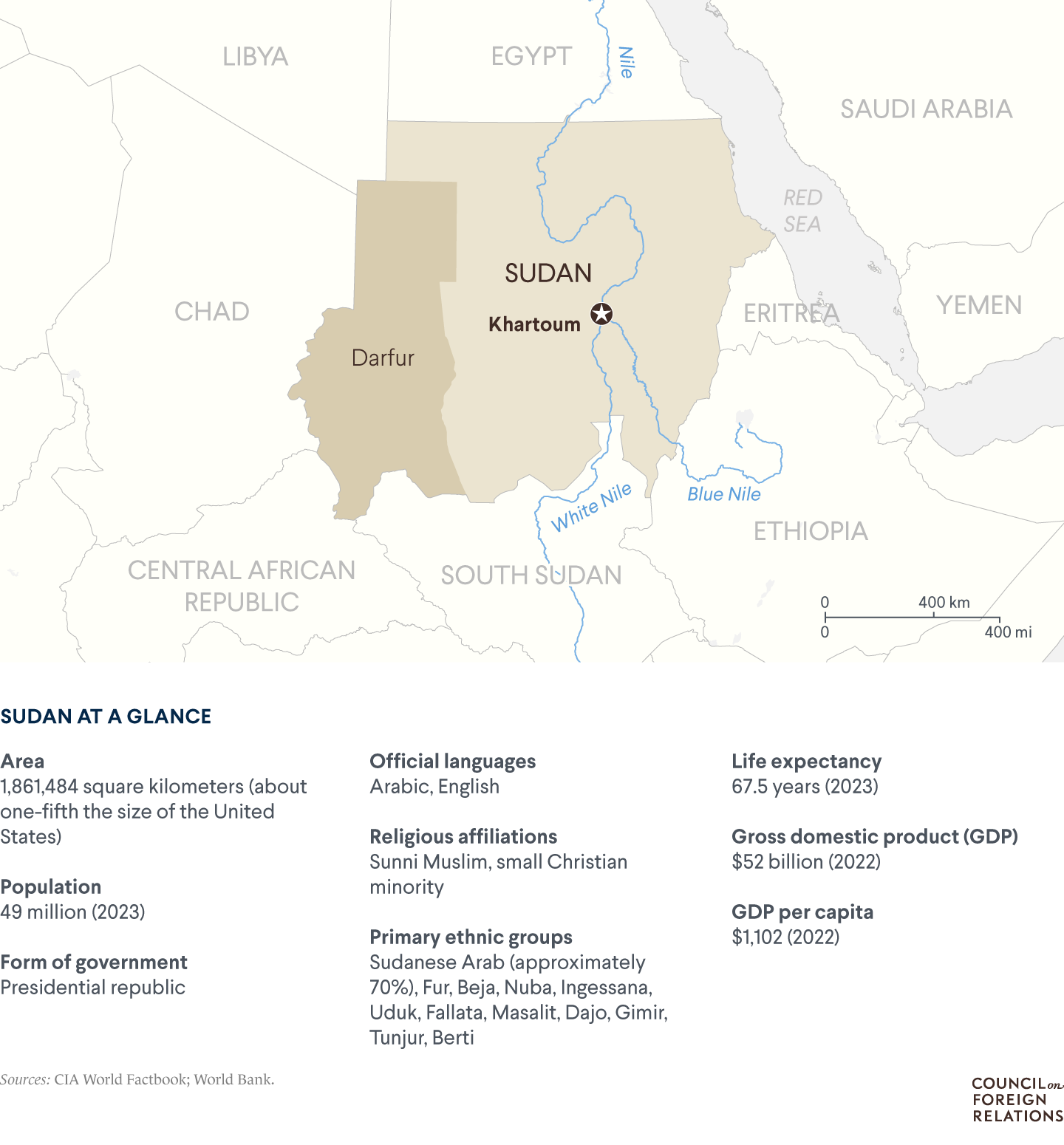

Sudan has been engulfed in civil war since fighting erupted on April 15, 2023, between the nation’s military, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and a paramilitary group known as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The violence has worsened an already precarious humanitarian situation, driving the spread of mass-starvation conditions. Meanwhile, neighboring countries have taken in more than one million refugees, risking broader destabilization across the Horn of Africa and Sahel regions.

What’s driving the conflict in Sudan?

The two warring parties were previously allies, having joined forces in 2019 to overthrow dictator Omar al-Bashir, who ruled for three decades before his ouster. The SAF’s leader, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, replaced him as de facto head of state. Burhan was backed by RSF General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, in orchestrating a second coup in 2021 that toppled Sudan’s interim government. But amid international pressure to transition to a civilian government, a push to integrate the RSF into the national army triggered a violent revolt from Hemedti in mid-April 2023. Fighting has been concentrated in and around the capital, Khartoum, the North and West Kordofan provinces, and the western Darfur region.

More on:

International efforts to broker peace talks or establish a caretaker government have been unsuccessful. These have included negotiations sponsored by the United States and Saudi Arabia, which resulted in at least sixteen failed cease-fires, as well as unsuccessful peace plans proffered by the African Union and other regional blocs. An Egypt-led conference with Sudan’s neighbors in July 2023 established humanitarian corridors and a framework for political dialogue, but it did not resolve the conflict, and both warring parties have hindered the delivery of aid, shutting down the corridors. Meanwhile, the Sudanese government has cut ties with the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a bloc of East African countries, over its outreach to RSF leader Hemedti, and has banned several foreign media outlets from the country.

Negotiation efforts remain at a standstill, though the United States says it aims to resume peace talks. In April 2024, France hosted a humanitarian conference that collected more than $2 billion in pledges of additional international aid.

How bad is the humanitarian situation?

Sudan was already experiencing a grave humanitarian crisis before the conflict broke out, with more than 15 million people facing severe food insecurity and more than 3.7 million internally displaced persons. The country was also hosting some 1.3 million refugees, the majority from South Sudan.

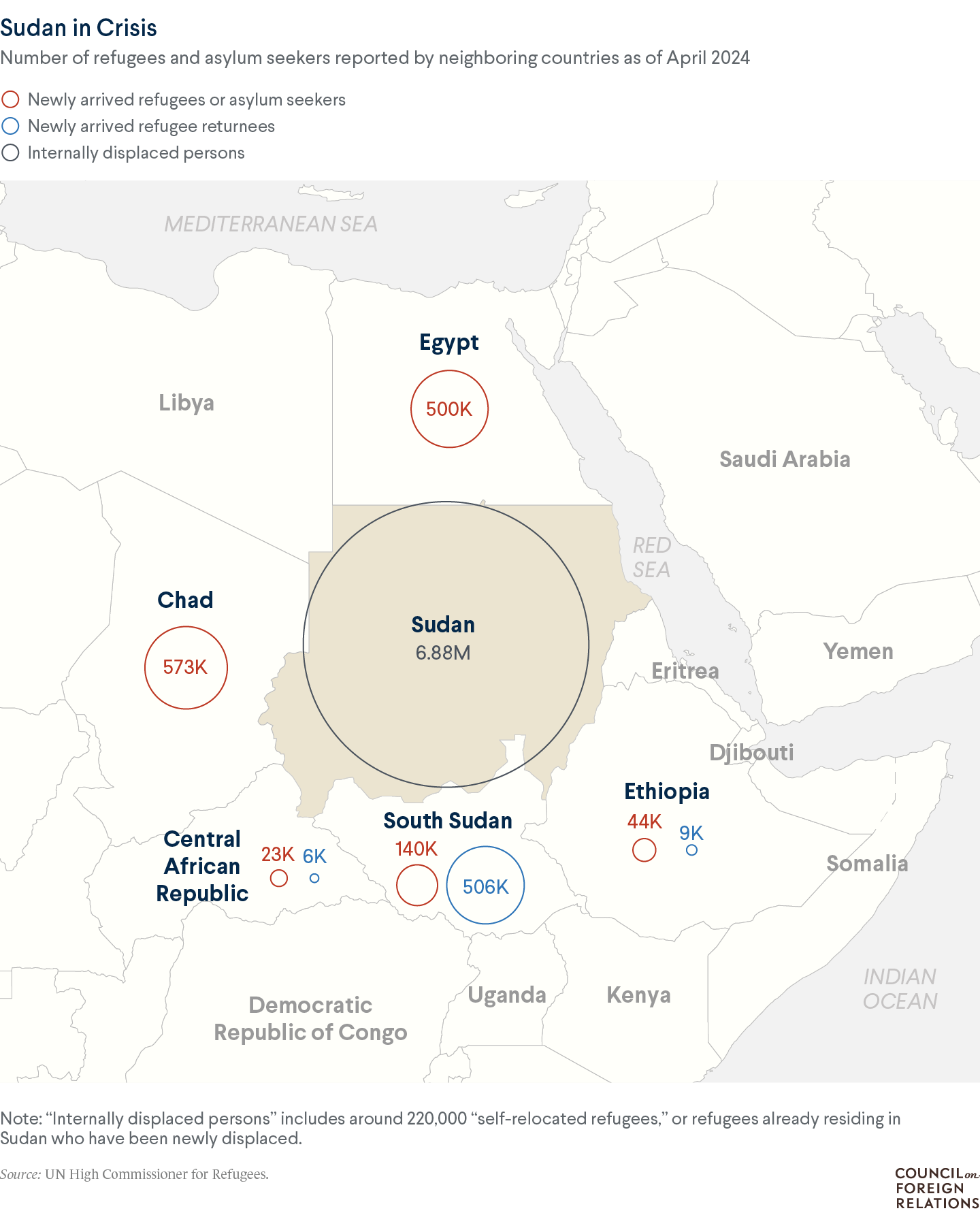

But amid the ongoing wars in the Gaza Strip and Ukraine, “Sudan keeps getting forgotten by the international community,” UN aid leader Martin Griffiths said in February 2024. According to the UN refugee agency, more than 8.6 million people have been forcibly displaced since April 2023. Of them, more than 6.6 million are internally displaced, while close to 1.8 million are refugees who have fled to neighboring countries. As of April 2024, more than fifteen thousand people have been confirmed killed in Sudan’s conflict, though the actual figure is likely to be considerably higher.

More on:

The conflict is destroying Sudan’s infrastructure. Air strikes and shelling have hit hospitals, prisons, schools, and other facilities in dense residential areas. The fear of disease is particularly acute, and health authorities have warned that cholera, dengue fever, and malaria are circulating in several states as health conditions continue to deteriorate rapidly and millions of people lack access to clean water. At the same time, rising food and fuel costs are exacerbating food insecurity, which currently affects nearly eighteen million people. The World Food Program says Sudan could become the site of “the world’s largest hunger crisis” without a cessation of hostilities. In total, almost twenty-five million people, or more than half of Sudan’s population, need aid and protection, according to UN estimates.

Where are refugees going?

More than 570,000 people, or 45 percent of all new refugees, have headed west to Chad. Another more than 500,000 refugees are South Sudanese who had previously fled to Sudan and have since returned to their home country due to this conflict. The remaining refugees have fled to the Central African Republic, Egypt, and Ethiopia, all of which have sizable refugee and internally displaced populations of their own.

UN experts say that Sudan is experiencing the world’s largest internal displacement crisis, and that the total number of refugees will keep growing as fighting continues. The majority of refugees are women and children, who are more vulnerable to sexual assault and gender-based violence. There have also been reports of ethnically driven mass killings and weaponization of sexual violence against the Masalit people, particularly in the West Darfur city of El Geneina. Both the SAF and RSF have been accused of war crimes, which a UN fact-finding mission is formally investigating.

How have neighboring countries responded?

Many of Sudan’s neighbors are still struggling to handle the influx of refugees on top of their own domestic headaches. Five of the seven countries bordering Sudan have recently suffered internal conflict, and refugees who previously fled violence and famine in Ethiopia and South Sudan are now returning to their home countries alongside Sudanese nationals.

In addition, concerns over foreign interference have grown as the conflict escalates. Egypt has close ties to the SAF, while Russia-backed Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar has sent military supplies to the RSF. The Sudanese army and U.S. lawmakers have also publicly accused the United Arab Emirates of providing military supplies to the RSF, which Abu Dhabi has denied.

The crisis has also presented a looming threat to regional economic cooperation on Nile River water resources and several major oil pipelines that cross through Sudan. Climate change has contributed to devastating drought and floods, heightening migrant displacement and upping the pressure on access to natural resources. The country’s ports along the Red Sea are also in a precarious position amid increasing attacks on vessels by the Iran-backed Houthi rebel movement in Yemen. The SAF has reportedly benefited from using Iran-made drones, though both Tehran and Khartoum deny having any direct connection.

UN experts say Sudan’s neighbors need far more assistance. The Central African Republic has called for more aid, as its own internal conflict has rendered it ill-equipped to handle incoming refugee flows. Chad closed its land border with Sudan immediately after fighting broke out but continues to aid refugees that make it across, though Chad itself is suffering from a lack of food aid. U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield said that Washington was pushing the UN Security Council to set up an aid delivery operation to Sudan through Chad. Egypt’s border remains open, but crossings are often delayed for days, and migrants there face immense challenges. Several countries in the Horn of Africa and Sahel regions—including Chad, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Kenya, and South Sudan—have participated in peace negotiations in hopes of stemming these issues at their source.

What have international organizations done?

A constellation of agencies, funds, and programs, collectively known as a UN Country Team (UNCT), has been in Sudan for years. Since the start of 2024, the United Nations and its humanitarian partners have provided life-saving assistance to more than two million people across the country, including food, water, and medical services, with the goal of reaching close to fifteen million people by the end of the year. Several other organizations, including CARE International, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and various Islamic relief agencies, are also supplying aid, in addition to the work being carried out by local Sudanese aid groups.

The conflict has forced the United Nations and aid organizations to temporarily halt or scale back in-country operations. The RSF captured the city of Wad Madani in Gezira state, a critical aid hub, in December 2023, further hampering aid delivery; that same month, the World Food Program suspended assistance in Gezira due to escalating violence. Other groups, such as the International Rescue Committee, have been forced to relocate their staff to safer areas. Meanwhile, funding shortfalls make it difficult to meet refugees’ needs. The United Nations’ 2024 appeal for $2.7 billion worth of aid for Sudan is only 6 percent funded; last year’s appeal fell far short of the $2.6 billion requested.

Will Merrow created the graphics for this In Brief.

Online Store

Online Store