The deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century scorched Lahaina, Hawaii.

In Libya, torrential rains fell in volumes rarely seen, leading to devastating floods that destroyed a quarter of the city of Derna.

Extreme heat struck Europe, where several countries shattered temperature records.

The Weather of Summer 2023 Was the Most Extreme Yet

Even compared to the intensifying severe-weather events of recent years, this season was exceptional, marked by historic heat, wildfires, and storms.

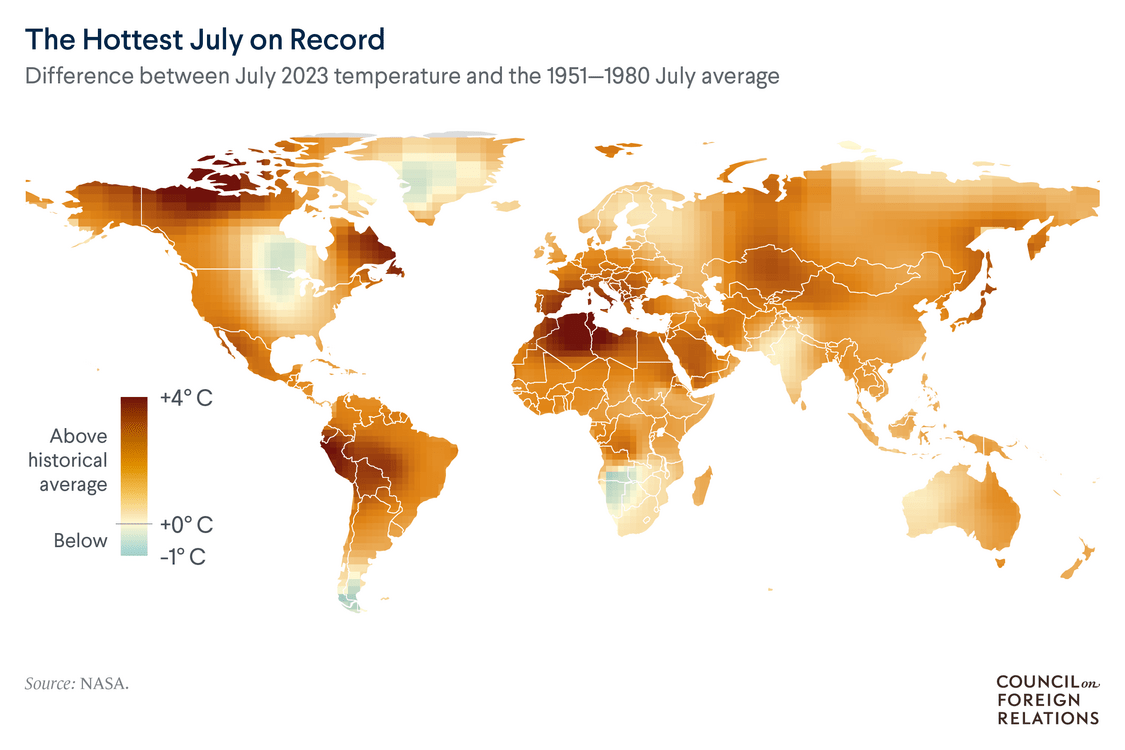

The summer of 2023 was the Northern Hemisphere’s hottest in recorded history. Scientists say the extreme heat, combined with other weather phenomena, contributed to this summer’s epic ocean storms, wildfires, flooding, and droughts. In North America and Europe, such heat would have been “virtually impossible” had humans not warmed the planet with fossil fuel emissions, according to World Weather Attribution, a group of scientists who analyze how climate change influences extreme weather. Experts warn that continued burning of fossil fuels will result in temperatures that break this year’s heat records, which have imposed widespread health and economic costs.

Record Heat and Humidity

The dog days of summer are not just barking, they are biting. Climate breakdown has begun.

In the United States, China, Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, temperatures set records, with lethal consequences for some of those unable to escape the heat. June through August marked the world’s hottest three-month period in recorded history, and the average global temperature in July was more than 2°F (1.1°C) hotter than last century’s average, according to the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “The dog days of summer are not just barking, they are biting,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres said. “Climate breakdown has begun.”

In many parts of the world, extreme heat has been accompanied by high humidity, which can cause dangerous rises in body temperature and cardiovascular strain. In the United States and the Middle East, the “wet-bulb” temperature, a measure of heat which includes humidity, reached levels scientists consider potentially deadly.

For elderly people and people with underlying conditions, high temperatures and humidity can be especially dangerous. The human impact of this summer’s heat is not yet fully known, but researchers estimate that last year’s less severe heat wave in Europe killed sixty thousand people. In the Netherlands, this year’s high temperatures coincided with a 5 percent increase in excess mortality.

Meanwhile, economists warn of the threat to growth. Some research has found that extreme heat is already costing the U.S. economy $100 billion annually, a price tag that could increase to $500 billion by 2050. These figures only take into account productivity lost when it is too hot to work, but extreme heat can also diminish crop yields, decrease tourism, raise health-care and energy costs, and damage infrastructure. A 2022 study by scientists at Dartmouth College found that extreme heat caused between $5 trillion and $29.3 trillion in global economic losses from 1992 to 2013.

Historic Wildfires

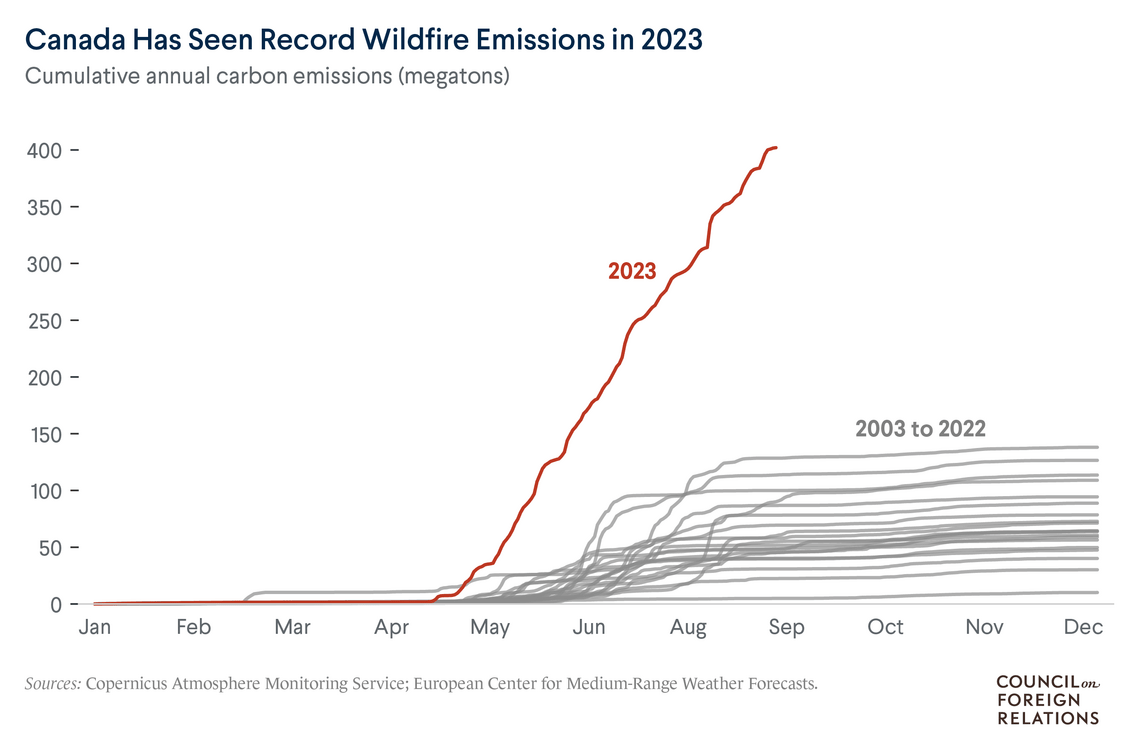

Unprecedented fires raged in the summer’s extreme conditions. In its worst-ever season, Canada doubled its previous record for carbon emissions from wildfire, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. In Europe, Greece recorded its most intense burst of wildfire emissions ever. And in the Pacific, a blaze in Maui, Hawaii, became the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century.

Hotter temperatures create drier conditions, allowing fires to ignite more easily, spread faster, and burn more intensely. This summer’s conflagrations incinerated tens of millions of acres in the United States, Algeria, Canada, and Greece, exposing hundreds of millions of people to potentially toxic airborne particles.

Plumes of smoke generated by wildfires diminished air quality for hundreds of miles. Smoky haze from wildfires in Quebec and Ontario reached more than one hundred million Americans in the northeast, midwest, and mid-Atlantic, contributing to the worst-ever air pollution for dozens of U.S. cities. Fires burning in the Pacific Northwest as of September 2023 could have the same effect for the western United States.

Wildfires threaten both public health and economic prosperity. The risk of a fatal heart attack doubles when extreme heat overlaps with poor air quality, according to the American Heart Association. In 2017, the U.S. government’s National Institute of Standards and Technology estimated the annual economic burden of wildfires to be between $71.1 and $347.8 billion in the United States alone.

Oceans of Trouble

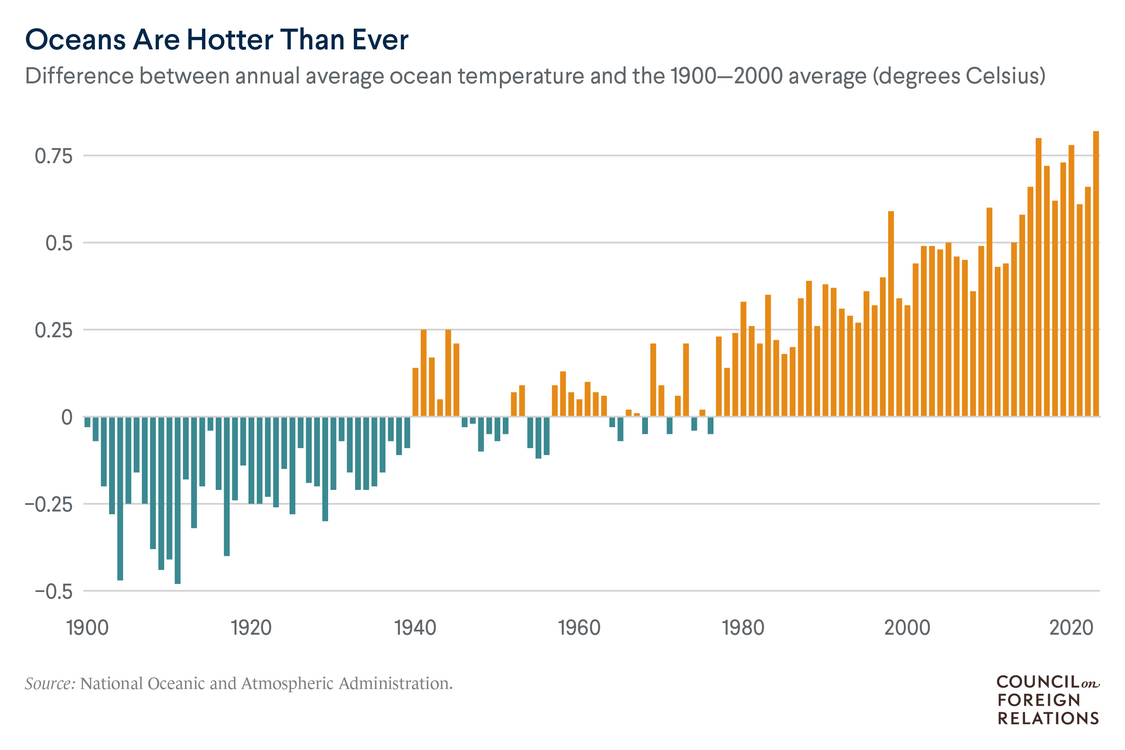

Sea temperatures also broke records this summer, with NOAA estimating that more than 40 percent of the world’s oceans are experiencing a so-called marine heat wave. The average global ocean surface temperature reached an all-time high.

Crucial ecosystems are at risk; coral bleaching off the coast of Florida began months earlier than usual and triggered fears of an ecologically destabilizing mass die-off. Bigger storms and accelerating sea-level rise continue to threaten coastal communities and the global economy. Without climate change adaptation, flood damage from rising sea levels could cost [PDF] up to $50 trillion annually across the world, or about 4 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP), according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Like rising air temperatures, ocean warming is predominantly caused by human activity; oceans absorb up to 90 percent of the heat generated by greenhouse gas emissions. According to a 2018 study [PDF] by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, higher ocean temperatures accounted for half the sea-level rise seen over the past fifty years. The United Nations calls higher sea levels a “threat multiplier” that can engender more dangerous hurricanes, typhoons, and floods. And even without storms, rising seas make flooding more likely. NOAA estimates that “sunny day” flooding now occurs twice as frequently in the United States as it did in 2000.

Twin Dangers: Flooding and Drought

Hot temperatures have spurred record precipitation across the globe. The deadliest-ever Mediterranean cyclone dropped record rainfall in Libya, overwhelming dams and causing catastrophic flooding; more than three thousand people have died with thousands more still missing.* In India, monsoon rains killed more than one hundred people. And in the United States, heavy rainfall caused Vermont’s worst floods in a century, while parts of Kentucky recorded their highest-ever totals for twenty-four-hour rainfall, according to NOAA. Overall, the summer’s flooding caused billions of dollars in damages.

Meanwhile, countries such as Chile and those in the Horn of Africa are facing their worst droughts in decades. (Extreme heat can worsen droughts by speeding evaporation, which reduces surface waters and dries out soil.) Like higher sea levels, droughts can exacerbate other severe weather events. Drier soil is less absorbent, making flooding more frequent and destructive. It can also increase the risk of wildfires by up to 80 percent, according to a study by the American Geophysical Union.

A Global Response?

Almost every country has signed the 2015 Paris Agreement, which seeks to limit global temperature increase to “well below” 2°C (3.6°F) above preindustrial levels. Experts say avoiding the worst impacts of climate change will require limiting that increase to 1.5°C (2.7°F) at most. But with heat-trapping emissions continuing to climb globally, scientists say the world will pass that benchmark in the next few years. July 2023 marked the first full month to exceed the 1.5°C limit while most of the world’s population experienced summer conditions, offering a preview of a world overheating. “Never has the destructive force of climate change revealed itself so widely across the globe,” CFR senior fellow Alice C. Hill writes.

Never has the destructive force of climate change revealed itself so widely across the globe.

Scientists agree that the best strategy to reduce global heating is to stop the accumulation of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere. Still, there are measures that can mitigate the effects of extreme heat. These include creating natural disaster early-warning systems, increasing shade coverage in urban areas, developing climate-adaptive crops, strengthening insurance coverage, increasing the availability of air conditioners, and investing in climate-resilient infrastructure. While this investment can carry large up-front costs, many economists believe it can save money in the long run by limiting the fallout from disasters. Meanwhile, some South American countries are expanding protections for the Amazon Rainforest, a massive carbon sink that absorbs about one-quarter of all the greenhouse gasses pulled from the atmosphere.

Efforts to grapple with the crisis in global fora continue, with experts calling for greater coordination between large emitters. “It is not clear how progress on mitigation at the scale and speed now needed is possible without coordination between China and the United States—the leading sources of greenhouse gases,” writes CFR senior fellow David P. Fidler.

World leaders are expected to discuss climate action in September 2023 at the United Nations’ Climate Ambition Summit, where they will present updated targets for reaching net-zero emissions, even as energy-exporting countries including the United States scale up fossil fuel production. The UN Global Stocktake report, released ahead of the summit, points out that countries have made some progress toward meeting climate goals, but it urges greater ambition as carbon continues to build in the atmosphere. And at the yearly UN climate conference in December (known as the twenty-eighth Conference of the Parties, or COP28), leaders are expected to discuss initiatives to reduce the consequences of extreme heat, including by expanding access to sustainable cooling technologies and infrastructure.

*A previous version of this piece cited numbers from the United Nations that have since been revised downward.

Recommended Resources

This Backgrounder looks at the Caribbean’s efforts to build climate resilience.

This Explainer video explores the consequences of a world warmed by 1.5°C.

For Foreign Affairs, CFR senior fellow Alice C. Hill argues that governments must now prepare for an age of extreme weather in addition to reducing emissions.

CFR expert David P. Fidler examines the muted global foreign policy responses to extreme heat in this Think Global Health article.

This CFR event proposes innovative solutions to the climate crisis.

This article explains how climate change is increasing the threat of zoonotic diseases.

Online Store

Online Store