The horrors of the Second World War spurred countries throughout the world to come together to draft the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). On December 10, this critical international instrument celebrates its seventy-fifth anniversary. In this Council of Councils global perspectives, seven experts reflect on the legacy of the declaration and offer insights into the role it should play amid an erosion of human rights, the outbreak of wars, a tsunami of emerging technologies, and instances of religious intolerance.

Time to Recognize a Beacon of Human Decency

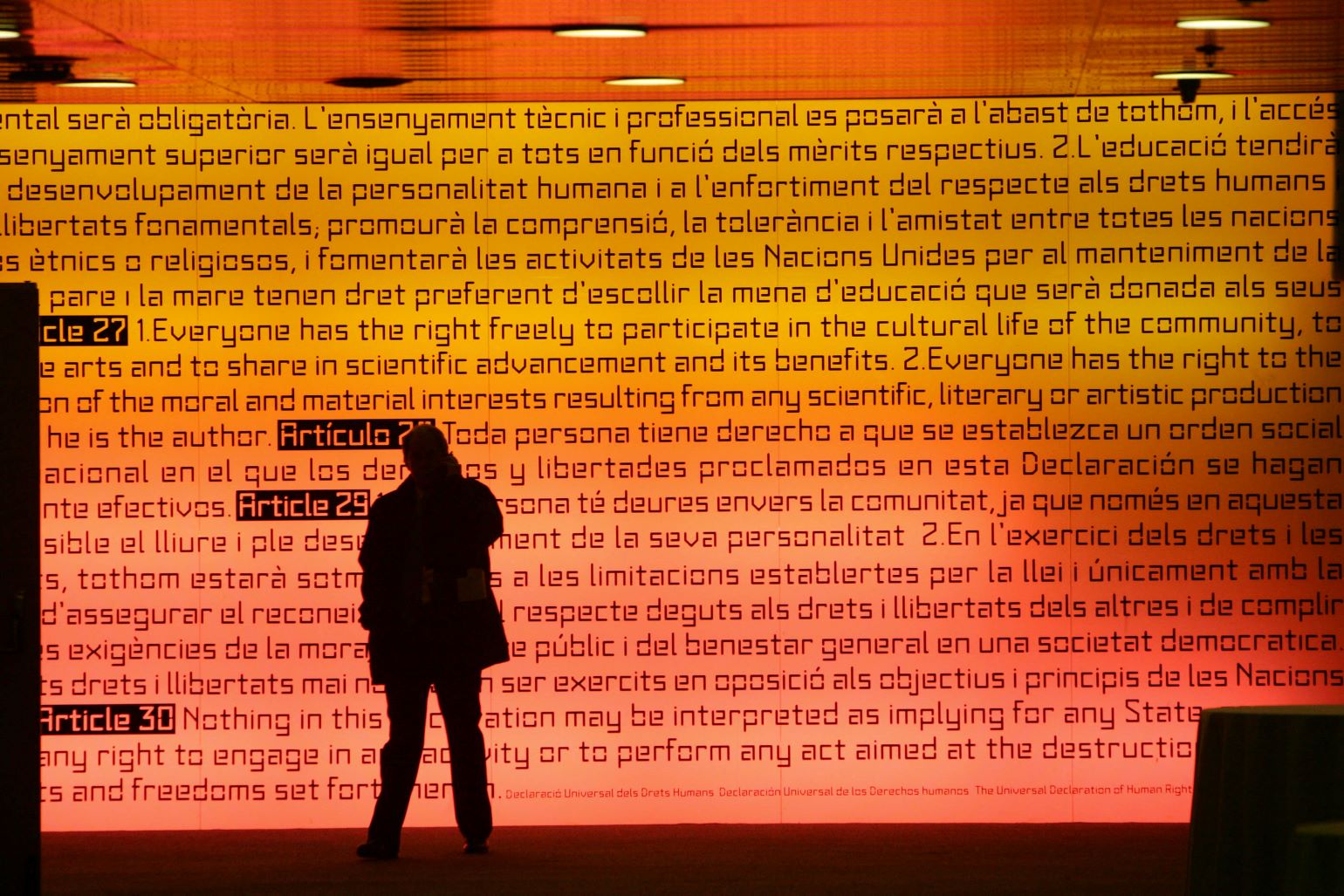

The seventy-fifth anniversary of the UDHR is a moment of both reflection on the past and of aspiration for the future. As an international instrument of governance, only the UN Charter could be regarded as having had more influence on the course of human events than the UDHR. Though its declaratory character falls short of being a binding treaty between states, the UDHR inspired the modern human rights movement and stands as a beacon of human decency to guide not only the conduct of governments, but also the lives of peoples and individuals who seek the protection of international human rights law.

The UDHR spurred the truly international negotiations leading to binding treaties such as the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. These three documents are often viewed as the “International Bill of Rights,” which together have had more impact on the global mindset than as enforceable law. Indeed, given the ideological divisions arising at the start of the Cold War when the UDHR was negotiated and approved by the UN General Assembly, its nonbinding character served that era well. There was more value in settling on universal standards of morality with essentially a collective nod among states than futilely attempting to codify standards as the world fractured into a postcolonial order dominated by the competition between capitalism and communism. An immediate plunge toward codification would have met roadblocks of opposition which, while voiced during the UDHR negotiations, were overcome with reliance upon the common sensical and moral reasoning of the final declaration.

Nonetheless, there are strong arguments afoot that the UDHR has entered the domain of customary international law and thus cannot be ignored by recalcitrant governments. The federal courts of the United States have often cited the UDHR to amplify the protection of human rights that are buttressed by binding treaties and U.S. law. The UDHR may not give an American standing to lodge a human-rights claim in court, but it is a potent instrument of advocacy once the victim stands before the judge.

The political mandate of the UDHR is set forth in Article 28: “Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.” That remains the mandate of the future and one that all countries should strive to achieve.

A Tough Road Ahead

As the world gears up to celebrate the anniversary of the UDHR, it makes sense to revisit the journey and briefly record the impact of this landmark document. Birthed in the aftermath of the horrors of the Second World War, the UDHR, which is characterized as the common language of humanity, has served well in bringing recognition and advancement of human rights across all regions of the world.

A clear testimony of this is that as many as 193 UN member states have ratified at least one of the treaties of UDHR. For many postcolonial states with long experiences of repression and violence, the UDHR and its enriching provisions on civil, political, social, and cultural human rights inspired them to frame human rights in their new constitutions. A good case is India. While the drafting of UDHR was in progress, many important conversations on that process informed India’s constitution-making process between 1947 and 1949. Some of the crucial members of the Constituent Assembly were also involved in the drafting process of UDHR. The clearest evidence of this convergence can be found in Part-III of the Indian constitution—named Fundamental Rights—which arguably remains the cornerstone of democratic governance. Beyond India, many democracies from the Global South adopted the UDHR and UN Charter as foundations for defining domestic rights.

While the UDHR has made an incredible impact in many countries, including non-democracies, many of its core principles and aspirations stand at a critical inflection point today. Ever-expanding geopolitical conflicts, civil wars, democratic backsliding in major democracies, growing autocratization, xenophobia, increasing political violence, and rising discrimination against minorities are testing the relevance of the UDHR and the human rights it enshrines.

The pace of the erosion of human rights has significantly accelerated as the United Nations and other global governance institutions become increasingly dysfunctional. This process is furthered by the visible decline of the Western liberal order, which, to a major extent, has led to widespread human rights violation in Afghanistan, China, Congo, Iran, and Myanmar, among others. Two ongoing wars (Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Israel’s ongoing conflict with Hamas) and the failure to prevent widespread human rights violations (particularly mounting civilian casualties) greatly strains the declaration and its mandate. Newer challenges are also emerging, such as climate change, emerging technologies, and artificial intelligence, all of which will need new imagination and framing in the UDHR. As it celebrates seventy-five years since its founding, the time has come to revalue and recharge the UDHR’s universal appeal.

Time for a Rebirth of the Rights Movement

Seventy-five years ago, from the ashes of a war that decimated most of Europe and large swathes of Asia and Africa, fifty countries adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. At the time, much of Africa and Southeast Asia were still under colonial rule, a newly independent South Asia was reeling from partition, and China’s decades-long civil war was nearing its conclusion. The Cold War had just started and would last a further forty-three years. In the Levant, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War was underway, and in South Africa apartheid was officially enacted into law.

This period speaks to the stark contrast between aspiration and reality. On the one hand, the Universal Declaration signaled a shared hope for a better world in which all people are equal, free, and have their fundamental rights protected, promoted, and respected. On the other, the harsh reality of a divided world at war.

Uphill as its battle has been, the Universal Declaration birthed a movement. The new human rights movement that emerged spearheaded global shifts that saw African countries attain their independence, the eventual end of the Cold War, and the dawn of global accountability. Nelson Mandela said it best when referring to the Universal Declaration coinciding with the start of apartheid: “the simple and noble words of the [Universal Declaration] were a sudden ray of hope at one of our darkest moments […] and proof that we were not alone.”

As 2023 ends with conflicts raging across Africa, Asia, and Europe, and a noted regression in the protection of the fundamental rights to life, dignity, and equality, one wonders how the Universal Declaration can breathe new and better life into a fragmented world.

At the core of the Universal Declaration is a reflection that equality, freedom, and justice for all are values that propel a society to thrive. Adhered to, the thirty articles of the Universal Declaration are the master code to a better world. Yet, global commitment—at local, national, regional, and international levels—is needed to unlock that world. From access to education, employment, voting rights, healthcare, housing, and social security to freedom from torture, the right to seek asylum, freedom of speech, rights to privacy, and mutual respect irrespective of gender, race, ethnicity, or religion, the true test lies in action.

This December, the UN Human Rights Office and member countries are expected to announce global pledges and the future vision for human rights. While much has changed in the world (a treaty-based system with a solid human rights architecture), much remains the same (conflict, inequality, and repression). Tackling exploitation, racism, apartheid, misogyny, and climate injustice remains key. The universal must still be brought to life through equality, freedom, and justice for all.

How Human Rights and Religion Can Work Better Together

From the beginning, the promise of the UDHR was about laying the foundation for a more peaceful and equitable world. For many countries in what is now called the Global South, this meant dealing with racism and religious intolerance must be at the top of the human rights agenda.

The story of human rights is often told in terms of the UDHR and the two covenants adopted in 1966—one on civil and political rights, the other on economic, social, and cultural rights. However, the historian Steven Jensen has shown that the real story is more complex. It was the covenant on racial discrimination that first brought human rights into international law in 1965, while a draft convention on religious intolerance sadly collapsed against the backdrop of the Six-Day War in 1967.

Today, the relationship between religion and human rights is fraught. Religious nationalist governments trample over minority rights, some religious groups attack the perceived liberal agenda of human rights, and secular human rights groups frequently disregard religion altogether. This is a travesty, for at least three reasons.

First, addressing religious intolerance is a pressing need in many parts of the world. Muslim minorities have faced particularly appalling hostility, whether in Xinjiang, China; India; or increasingly across Europe. But virtually all religious communities face discrimination and hostility as a minority somewhere.

Second, protecting the rights of minorities is a condition for successful democracies. In the context of rancorous divisions that often exploit the politics of identity, religious minorities are profoundly vulnerable to being othered by governments and treated as second-class citizens or blamed for social ills. The treatment of minorities—racial and religious—should be a vital measure of the health of a democracy.

Third, religious beliefs—and communities of religious people—offer deep resources to help advance peace, justice, and equality. While the UDHR and international human rights law send few pulses racing, religious language provides a way for people to express their deepest yearnings for a fairer and more just world. For example, some critiques of artificial intelligence (AI) use semi-religious language such as affirming a need to protect the soul of humanity.

In the end, fulfilling the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion for everyone will come down to political will—whether people can look beyond the apparent self-interest of their own group and recognize that a much better world is possible if they can recognize themselves in the other.

AI, Freedom of Thought, and Human Rights

The acceleration of developments in AI over the past year has been accompanied by calls for global regulation. A tsunami of hype has promised either a technological utopia in a world free of work or a dystopia where our robot servants turn on us, but little focus on the existing frameworks in place to meet the new challenges of technology.

The UDHR, agreed to in a rare moment of global unity seventy-five years ago, paved the way for binding legal instruments like the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, which put the rights needed to enjoy full humanity into international law. Moreover, the UDHR contains a suite of rights and freedoms that resonate with and provide answers to the challenges of today.

Specifically, we need the absolute right to freedom of thought to protect the inner sanctum of our minds now and for the future. Social media algorithms that understand our preferences and use them to profile and target us to affect our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors have implications for our rights to freedom of thought and opinion set out in Articles 18 and 19 of the UDHR. Developments like neurotechnology—which purports to read our minds directly or affect the functioning of our brains—could be new, but new rights are not required to address them.

Generative AI is trained on the entirety of human creativity, knowledge, and nonsense scraped from the internet. This raises serious questions about the protection of the moral and material rights of creators set out in Article 27 of the UDHR, as their labor goes unrecognized and unpaid. The same article gives us all the right to share in scientific advancement and its benefits. And AI works on the labor of people around the world who build the hardware and train the software in work conditions that flout many other rights to rest, reasonable pay, and the right to form unions while AI is used to put others out of work.

It is not that these rights are outdated in the twenty-first century, it is that they are ignored. We don’t need new rights or new regulators, we need to make sure that the rights we already have, exemplified in the UDHR, are respected and made real and effective in the world of big technology.

Taking the UDHR as a Common Basis of Building a Human International Order

In recent years, the world has faced extreme turbulence, with both traditional and nontraditional security challenges intertwined. The new Middle East conflict erupts while the bloody war in Ukraine is still ongoing, the two killing hundreds of thousands of people and making more homeless. In addition, the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, stagnant global economic growth, and emerging food, energy, and environmental crises make protecting human rights an even tougher task.

There are many reasons for the current deterioration in global governance. Hegemony, major power rivalry, reginal conflicts, unjust and unequal international order—different countries have different answers. Nevertheless, there are very few, if any, who would question or challenge the necessity and urgency of human rights protection. At this critical moment, the UDHR, the cornerstone of international human rights regimes, is arguably the biggest common denominator for the global system of states. Therefore, it is extremely important to commemorate its seventy-fifth anniversary and reflect on how the UDHR can meet the needs of our time and advance its promise of freedom, equality, and justice for all.

China has been a key supporter and contributor to the UDHR since its very beginning. Dr. Peng-chun Chang, a prominent Chinese educator and senior diplomat who grew up in Chinese culture and received his PhD from Columbia University, was one of the nine members who drafted the UDHR, and played a crucial role in introducing principles of Confucian thought including conscience, benevolence, and inclusiveness into the UDHR, making it the first international human rights canon combining the wisdom of Eastern and Western civilizations.

To further the UDHR, China and more than seventy other countries have suggested a number of revisions and expansions. Specifically, that civil and political rights, and economic, social, and cultural rights should be accorded equal attention and advanced in a holistic way; human rights should be pursued in a results-oriented way with an emphasis on sustainable development; human rights development should suit the realities of each country, respecting their historical background, cultural heritage, national conditions, and popular needs; and that human rights advancement should be based on constructive dialogue and cooperation rather than used as a tool of political manipulation and bloc confrontation. In practice, China has put forward three global initiatives consecutively in the past three years: the Global Development Initiatives, Global Security Initiatives, and Global Civilization Initiatives. The logic within each is that human rights can be better protected and advanced with a condition of global security, sustainable development, and mutually respectful civilizations. UDHR includes all those values and thus can be taken as a common basis for building a humane international order.

A Humanity-Centered Approach to International Law

The UDHR was adopted as a law and principle for all people, setting off an extraordinary expansion of international law. Modern international law can no longer be limited to the strict postulates of traditional conventional international law, and the current global architecture increasingly recognizes the importance of the relevant principles of international law in light of the fundamental considerations of humanity. The realization of human rights has evolved from the UDHR’s 1948 declaration through to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. More than seventy treaties are now in force protecting human rights at the global and regional levels, and the UDHR remains at the center of this complex architecture of rules, institutions, and mechanisms of protection.

Freedom, justice, and peace —the pillars of the 1948 universal declaration—guide the movement for human rights, and are how individuals are internationally protected. Enforcement remains a challenge, particularly for the massive violations of international law and human rights that occur in armed conflicts, but the existence of the UDHR and other similar treaties embodies the hope that the aspirations of humanity can gradually become reality. For those reasons, the UDHR has a direct impact on the day-to-day lives of people around the world. The ideas in the UDHR support modern conceptions of human dignity, peace, and sustainable development.

Human dignity. Evidently, the progress and development of human rights has had a direct impact on the current status of international law and established a more humanistic form of rights—the right to be treated in a humane and dignified manner by virtue of one’s common humanity. Individuals are surely guaranteed these rights through the fundamental concepts of international law.

Peace. Undeniably, peace is a duty and inherent right of all human beings. The basic idea underlying this is the recognition that the objective character of the 1948 Universal Declaration—the expression of the fundamental unity of international law—is inherent to the exercise of individual rights. This recognition reflects the conscience of humankind and is a fundamental pillar of the international law of human rights.

Sustainable development. Finally, the future of international human rights is in the 2030 Agenda. The agenda set out a vision for sustainable development based on international human rights standards, equality, and nondiscrimination. If the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals does not uphold those ideals, progress will ultimately prove to be illusory.