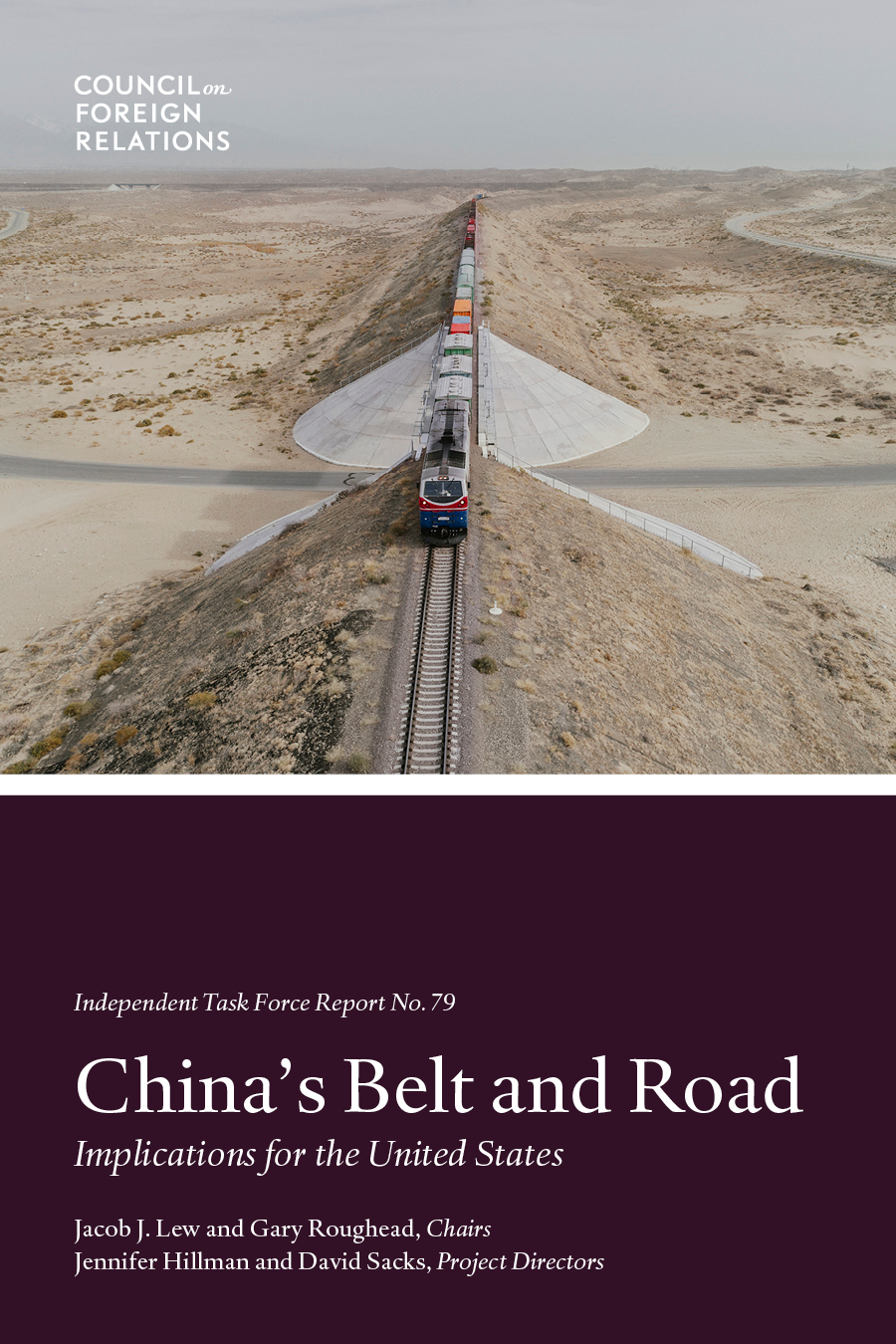

“The Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy undertaking and the world’s largest infrastructure program, poses a significant challenge to U.S. economic, political, climate change, security, and global health interests.”

Executive Summary

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy undertaking and the world’s largest infrastructure program, poses a significant challenge to U.S. economic, political, climate change, security, and global health interests. Since

BRI was initially designed to connect China’s modern coastal cities to its underdeveloped interior and to its Southeast, Central, and South Asian neighbors, cementing China’s position at the center of a more connected world. The initiative has since outgrown its original regional corridors, expanding to all corners of the globe. Its scope now includes a Digital Silk Road intended to improve recipients’ telecommunications networks, artificial intelligence capabilities, cloud computing, e-commerce and mobile payment systems, surveillance technology, and other high-tech areas, along with a Health Silk Road designed to operationalize China’s vision of global health governance.Assessing China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative</a>,” Council on Foreign Relations." href="#footnote1_hO6aUYjYRBLz">1 Hundreds of projects around the world now fall under the BRI umbrella.

China pursued BRI out of a belief that the initiative could simultaneously address a number of issues, including

- closing the gap between the country’s affluent coastal cities and its impoverished interior, thus boosting domestic political stability;

- absorbing its excess manufacturing capacity;

- putting its accumulated savings to work;

- securing a consistent source of inputs for its manufacturing sector; and

- reorienting global commerce away from the United States and Western Europe toward China.

The Task Force finds that China is advancing this initiative in worrying ways that

- undermine global macroeconomic stability and increase the likelihood that debt crises will materialize over the coming years by largely eschewing debt sustainability analysis and funding economically questionable projects in heavily indebted countries;

- subsidize privileged market entry for state-owned and non–market oriented Chinese companies;

- enable China to lock countries in to Chinese ecosystems by pressing its technology and preferred technical standards on BRI recipients;

- ensure countries’ dependence on carbon-intensive power for decades through its export of coal-fired power plants, making climate change mitigation significantly more difficult;

- make it harder for the World Bank and other traditional lenders to insist on high standards by offering quick and easy infrastructure packages that forego rigorous environmental- and social-impact assessments, ignoring project management best practices and tolerating corruption; and

- leave countries more susceptible to Chinese political pressure while giving China a greater ability to project its power more widely.

U.S. inaction as much as Chinese assertiveness is responsible for the economic and strategic predicament in which the United States finds itself. U.S. withdrawal helped create the vacuum that China filled with BRI. Although the United States long ago identified an interest in promoting infrastructure, trade, and connectivity throughout Asia and repeatedly invoked the imagery of the Silk Road, it has not met the inherent needs of the region.A Farewell to Flashman: American Policy in the Caucasus and Central Asia</a>,” U.S. Department of State, July 21, 1997; Condoleezza Rice, “<a href=https://www.cfr.org/task-force-report/"http://2001-2009.state.gov/secretary/rm/2005/54913.htm">Remarks at Eurasian National University</a>,” U.S. Department of State, October 13, 2005; and Hillary Rodham Clinton, “<a href=https://www.cfr.org/task-force-report/"https://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2011/07/168840.htm">Remarks on India and the United States: A Vision for the 21st Century</a>,” U.S. Department of State, July 20, 2011." href="#footnote2_nI7W9nJMnNq0">2 Its own lending to and investment in many BRI countries was limited and is now declining. Its cutbacks in research and development and investments in advanced technologies have allowed China to move ahead in the development and sale of fifth-generation (5G) technology, the installation of high-speed rail, the production of solar and wind energy, the promulgation of electronic payment platforms, the development of ultra-high-voltage transmission systems, and more. Despite enjoying a leading role in the World Bank and regional development banks, the United States has watched those institutions move away from backing significant infrastructure projects. Washington has not joined regional trade and investment agreements that would have enhanced U.S. economic ties to Asia.

These collective shortcomings allowed China to tap into a legitimate need around the world for new infrastructure and to fill the gap in infrastructure financing and construction in a way that benefits it. Beijing’s ability to offer hard and digital infrastructure around the world at low prices is made possible by a combination of political backing from the Chinese Communist Party, the financial power of its state-owned banks, excess capacity in a number of important sectors, and its development of large, highly capable manufacturing and technology companies. If BRI meets little competition or resistance, Beijing could become the hub of global trade, set important technical standards that would disadvantage non-Chinese companies, lock countries into carbon-intensive power generation, have greater influence over countries’ political decisions, and acquire more power-projection capabilities for its military.

The United States has a clear interest in adopting a strategy that both pressures China to alter its BRI practices and provides an effective alternative to BRI—one that promotes sustainable infrastructure, upholds high environmental and anticorruption standards, ensures U.S. companies can operate on a level playing field, and assists countries in preserving their political independence.

To do so, the Task Force recommends a four-pronged strategy: address specific economic risks posed by BRI; improve U.S. competitiveness; work with allies, partners, and multilateral organizations to better meet developing countries’ needs; and act to protect U.S. security interests in BRI countries. The United States cannot and should not respond to BRI symmetrically, attempting to match China dollar for dollar or project for project. Instead, the United States should focus on those areas where it can offer, either on its own or in concert with like-minded nations, a compelling alternative to BRI. Such an alternative would leverage core U.S. strengths, including cutting-edge technologies, world-class companies, deep pools of capital, a history of international leadership, a traditional role in setting international standards, and support for the rule of law and transparent business practices.

To mitigate the economic risks of BRI, the Task Force recommends

- leading a global effort to address emerging BRI-induced debt crises and to promote adherence to high-standards lending practices;

- enhancing U.S. commercial diplomacy to promote U.S. high-quality, high-standards alternatives to BRI and to raise public awareness in host countries of the environmental and economic costs of certain BRI projects;

- offering technical support to BRI countries to help them vet prospective projects for economic and environmental sustainability; and

- embarking on a robust anticorruption campaign.

To improve U.S. competitiveness, the Task Force recommends

- devoting an additional $100 billion toward federal research and development funding, with further investments in universities and research institutions to fund cutting-edge research, and enhanced support for private-sector investment in next-generation technologies;

- increasing investment in basic science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education at all levels;

- amending immigration and visa policies to make it easier to attract and retain the world’s brightest students, researchers, scientists, and engineers;

- improving coordination and providing greater support for participation in international standards-setting bodies;

- reforming the Development Finance Corporation and the Export-Import Bank of the United States by providing them with greater flexibility to compete with BRI’s offerings and to partner with other development finance institutions from around the world; and

- promoting U.S. digital transformation alternatives to the developing world.

To strengthen the multilateral response to BRI, the Task Force recommends

- working with allies and partners to reenergize the World Bank so that it can offer a better alternative to BRI;

- negotiating sectoral trade agreements with important regional partners, starting with digital trade agreements, and working to improve and then join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership; and

- insisting that China live up to its pledges for a green belt and road by requiring pre-project environmental assessments, denying financing or insurance to projects likely to have significant adverse environmental effects, and adopting binding standards for what constitutes a green BRI investment.

To protect U.S. security interests in BRI countries, the Task Force recommends

- creating mitigation plans for possible Chinese disruption of critical infrastructure in BRI countries;

- investing in undersea cables and undersea cable security; and

- training cyber diplomats who can work with host governments to reduce cyber vulnerabilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made a U.S. response to BRI all the more needed and urgent. The global economic contraction has revealed the flaws of China’s BRI model, forcing a reckoning with concerns that many BRI projects not economically viable and elevating questions of debt sustainability. Unless BRI-related debt is addressed, countries that are already being battered by the COVID-19 pandemic could be forced to choose between making debt payments and providing health-care and other social services to their citizens.

- 1“<a href="http://cfr.org/china-digital-silk-road">Assessing China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative</a>,” Council on Foreign Relations.

- 2Strobe Talbott, “<a href="http://1997-2001.state.gov/regions/nis/970721talbott.html">A Farewell to Flashman: American Policy in the Caucasus and Central Asia</a>,” U.S. Department of State, July 21, 1997; Condoleezza Rice, “<a href="http://2001-2009.state.gov/secretary/rm/2005/54913.htm">Remarks at Eurasian National University</a>,” U.S. Department of State, October 13, 2005; and Hillary Rodham Clinton, “<a href="https://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2011/07/168840.htm">Remarks on India and the United States: A Vision for the 21st Century</a>,” U.S. Department of State, July 20, 2011.

At a Glance

BRI seeks to back an array of projects, but to date, the vast majority of funds has been allocated toward traditional infrastructure—energy, roads, railways, and ports. Though principally aimed at developing countries, with Pakistan, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka among the largest recipients of BRI funds, BRI also includes developed countries, with numerous U.S. allies participating. If these U.S. allies were to turn to BRI to build critical infrastructure, such as power grids, ports, or telecommunications networks, this could complicate U.S. contingency planning and make coming to the defense of its allies more difficult.

Bookstores: To order bulk copies, please contact Ingram.

Visit ipage.ingrambook.com, call 800.937.8200, or email [email protected].

About the Task Force

Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs

Hoover Institution, Stanford University

Senior Fellow for Trade and International Political Economy, CFR

Research Fellow, CFR

Independent Task Force Program Director, CFR

Task Force Members

-

B. Marc Allen

B. Marc Allen -

Charlene Barshefsky WilmerHale

Charlene Barshefsky WilmerHale -

Brendan P. Bechtel Bechtel Group, Inc.

Brendan P. Bechtel Bechtel Group, Inc. -

Charles Boustany Jr. Capitol Counsel, LLC

Charles Boustany Jr. Capitol Counsel, LLC -

L. Reginald Brothers Jr. NuWave Solutions

L. Reginald Brothers Jr. NuWave Solutions -

Joyce Chang JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Joyce Chang JPMorgan Chase & Co. -

Evan A. Feigenbaum Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Evan A. Feigenbaum Carnegie Endowment for International Peace -

Jennifer Hillman (project codirector) Council on Foreign Relations

Jennifer Hillman (project codirector) Council on Foreign Relations -

Christopher M. Kirchhoff Schmidt Futures

Christopher M. Kirchhoff Schmidt Futures -

Jacob J. Lew (co-chair) Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs

Jacob J. Lew (co-chair) Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs -

Natalie Lichtenstein Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies

Natalie Lichtenstein Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies -

Gary Locke Bellevue College

Gary Locke Bellevue College

-

Oriana Skylar Mastro Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University

Oriana Skylar Mastro Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University -

Daniel H. Rosen Rhodium Group

Daniel H. Rosen Rhodium Group -

Gary Roughead (co-chair) Hoover Institution, Stanford University

Gary Roughead (co-chair) Hoover Institution, Stanford University -

David Sacks (project codirector) Council on Foreign Relations

David Sacks (project codirector) Council on Foreign Relations -

Nadia Schadlow Hudson Institute

Nadia Schadlow Hudson Institute -

Rajiv J. Shah Rockefeller Foundation

Rajiv J. Shah Rockefeller Foundation -

Kristen Silverberg Business Roundtable

Kristen Silverberg Business Roundtable -

Taiya M. Smith Climate Leadership Council

Taiya M. Smith Climate Leadership Council -

Susan A. Thornton Yale Law School

Susan A. Thornton Yale Law School -

Ramin Toloui Stanford University

Ramin Toloui Stanford University -

Macani Toungara

Macani Toungara -

Frederick Tsai Liferay

Frederick Tsai Liferay

Observers

-

Paul J. Angelo Council on Foreign Relations

Paul J. Angelo Council on Foreign Relations

-

Alyssa Ayres George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs and Council on Foreign Relations

Alyssa Ayres George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs and Council on Foreign Relations -

Robert C. Francis Jr. Council on Foreign Relations

Robert C. Francis Jr. Council on Foreign Relations

-

Michelle Gavin Council on Foreign Relations

Michelle Gavin Council on Foreign Relations

-

Joshua Kurlantzick Council on Foreign Relations

Joshua Kurlantzick Council on Foreign Relations

-

Mira Rapp-Hooper

Mira Rapp-Hooper -

Anya Schmemann Council on Foreign Relations

Anya Schmemann Council on Foreign Relations -

Benn Steil Council on Foreign Relations

Benn Steil Council on Foreign Relations

-

Jennifer Hendrixson White

Jennifer Hendrixson White